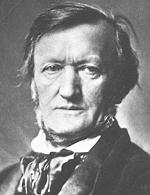

RICHARD WAGNER

22nd May 1813 --- 13th February 1883

Copyright 1994-1998 Encyclopaedia Britannica

Last Updated on December 2025

By Steven Ritchie

And now for the Music

(3834)"Swan Song from Lohengrin". Sequenced by R.Steven Ritchie.

(3477)"The Flying Dutchman (Selection)". Sequenced by R.Steven Ritchie.

(3466)"Die Meistersingers (Selection)". Sequenced by R.Steven Ritchie.

(3450)"Entrance of the Gods into Valhalla". Sequenced by R.Steven Ritchie.

(3448)"Selection from Lohengrin". Sequenced by R.Steven Ritchie.

(3044)"Spinning Song (from The Flying Dutchman)". Sequenced by R.Steven Ritchie.

(2537)"Tannhaeuser". Sequenced by R.Steven Ritchie.

NEW (4845)"All I know the file is named Process". Sequenced by Bill King.

NEW (4844)"Piano version of Ride of the Valkeries". Sequenced by W.Pepperdine.

NEW (4843)"Gotterdammerung, Sunrise". Sequencer Unknown.

Thanks to Yu Nakajima for the music below. Email (GCD02321@nifty.ne.jp)

(4270)"Lohengrin Vorspiel, Mov.1". Sequenced by Yu Nakajima.

(4269)"Lohengrin Vorspiel, Mov.3". Sequenced by Yu Nakajima.

(2075)"Tannhaeuser Overture". Sequenced by Yu Nakajima.

Thanks to Santiago Schleh for the music below. Email (santiagus @ hotmail com)

(4268)"Leb wohl & Feuerzauber". Sequenced by Santiago Schleh.

(3833)"The Valkyrie, Prelude Act.1". Sequenced by Santiago Schleh.

(3832)"The Valkyrie, Act.2". Sequenced by Santiago Schleh.

(3831)"Farewell & fire magic". Sequenced by Santiago Schleh.

Thanks to Frank McCormick for the music below. Email (mcfrank @ interaccess com)

(3447)"Descent to Nibelheim". Sequenced by Frank McCormick.

Thanks to Reinhold Behringer for the music below.

(3446)"Tristan, Siegfried, and Isolde". Sequenced by Reinhold Behringer.

(3041)"Liebestod uit Tristan und Isolde". Sequenced by Robert Finley.

(3043)"Not sure of the name of this piece". Sequenced by Fabrizio Calzaretti.

Thanks to Emily Gray for the music below. Email (HappyMusician@opendiary.com)

(1892)"Chorale from, Die Meistersinger". Sequenced by Emily Gray.

Thanks to Robert W. Losin for the music below.

(3040)"Entrance of the Gods into Valhalla". Sequenced by Robert W. Losin.

(756)"Siegfried's Funeral Music, Gotterdammerung Act.3". Sequenced by Robert W. Losin.

(1491)"Siegfried's Rhine Journey". Sequenced by Robert W. Losin.

(1490)"Prelude to Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg". Sequenced by Dr.David Siu.

(1493)"Traume". Sequenced by Ken Gilliland.

(1492)"Overture to Tannhsuser und der Ssngerkrieg auf Wartburg". Sequenced by L.Roberts.

(758)"Ride of the Valkyries". Sequenced by L.Roberts

(1494)"Rienzi Overture (1840)". Sequenced by David Sui.

(3042)"Tristan und Isolde, Introduction". Sequencer Unknown.

(759)"Meistersinger von Nurnberg". Sequencer Unknown.

If you done any Classical pieces of say for example, Delius, mozart, and so on etc,

please email them to the classical music site with details to

"classical (@) ntlworld.com" written this way to stop spammers

just remove spaces and brackets for email address, thank you.

Visitors to this page --

Back to Classical Midi Main Menu click "HERE"